The last

time I taught my Utopias half unit, in late 2011, we were in the middle of the

international Occupy movement. Lancaster

had its own Occupy camp, in Dalton Square, and one of my students would cycle

in from it to our seminar on A Modern

Utopia or Herland, and then pedal

busily back to her tent in town to continue the protest. This time round, we are in the midst of

significant political events again, though not of the same international

scale. For the academic pensions strike

is well under way at sixty-odd British universities, and this is becoming as

much a general political protest against the neo-liberal diminution of the very

idea of the university as it is a strike on a specific financial issue.

Two of my

Utopias seminars have fallen casualty to the strike, though I hope the students

have been reading and pondering the texts none the less. The two books involved have certainly been much

on my mind during these weeks of industrial action. The first is Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, in my view the

greatest of the 1970s utopias. One

sentence in particular leaps out at me, as I re-read under these new

circumstances. After leaving his

anarchist utopia Anarres for capitalist dystopia Urras, Shevek finally makes

contact with the political resistance there and informs them: ‘I came here

because they talk about the lower classes, the working classes, and I thought

that sounds like my people. People who

might help each other’. Well, the kind

of white working-class community in which I grew up half a century or so ago

barely exists in its old form any more, but new communities form themselves in

new struggles; and certainly the Lancaster University union picket line, as it

has evolved over the last few weeks, has come to feel like ‘my people. People who might help each other’.

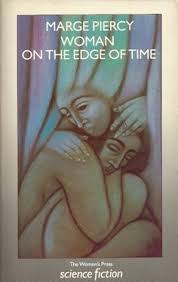

The second

text which will not now get discussed in our seminars is Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, a raw and

powerful book which I have not re-read for several years. Piercy runs utopian time-travelling in the

opposite direction to Bellamy and Morris: Luciente here travels back from a utopian future to the racist

nightmare which is the 1970s New York faced by Connie Ramos. The utopian visitor from Matapoisett brings

hope and wisdom, but she is a frail ontological presence too: ‘We are only one

possible future. Do you grasp?’ For it turns out that the utopians need

Connie as much as she needs them: ‘You may fail us … You of your time … You of

your time may fail to struggle altogether’.

Or, as Luciente had earlier asked her: ‘How come you took so long to get

together and start fighting for what was yours?’

That is a

question we on the picket line have been asking ourselves too. How has it taken so long to mount collective

resistance to the neo-liberal university on this scale? For in and beyond the pensions issue itself,

we are now fighting for utopia too: for a transformed notion of the university

which would break from the marketised dystopia of the present, without just

reverting to old-style liberal definitions of the institution either. This is as yet a frail utopia, facing

enormous hostile political and economic forces.

Yet if the new community of resistance which has come into being remains

‘true to one another’ – to wrench Matthew Arnold’s phrase from ‘Dover Beach’

out of context – and if we can involve our students in our arguments and

vision, then perhaps we too can open the present to intimations of a better

future.