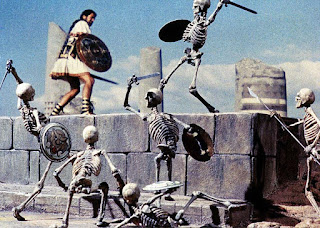

As a child I

used to enjoy watching the 1963 stop motion animation film of Jason

and the Argonauts on the television with my father; for the time - in those

far-back pre-CGI days - it was very striking in its visual effects.

So today I can enjoy reading Morris’s Life and Death of Jason (1867) for the sake of comparison and contrast with that twentieth-century version, though I can well understand that for many contemporary readers its rhythms are so flat and mellifluous that they may send you to sleep after just a few pages. It’s something of a truism in the modern criticism of Victorian narrative poems based on myth, legend or history that they only truly come to life if underlying psychic impulses of the author’s own get caught up in the act of composition. Thus Matthew Arnold’s mini-epic Sohrab and Rustum has what impact it still has, it is argued, because the son of the formidable Dr Arnold of Rugby had his own powerful fears about fathers destroying their sons’ identities, as happens literally in the poem when the great warrior Sohrab unknowingly kills his son Rustum.

So today I can enjoy reading Morris’s Life and Death of Jason (1867) for the sake of comparison and contrast with that twentieth-century version, though I can well understand that for many contemporary readers its rhythms are so flat and mellifluous that they may send you to sleep after just a few pages. It’s something of a truism in the modern criticism of Victorian narrative poems based on myth, legend or history that they only truly come to life if underlying psychic impulses of the author’s own get caught up in the act of composition. Thus Matthew Arnold’s mini-epic Sohrab and Rustum has what impact it still has, it is argued, because the son of the formidable Dr Arnold of Rugby had his own powerful fears about fathers destroying their sons’ identities, as happens literally in the poem when the great warrior Sohrab unknowingly kills his son Rustum.

So when Morris’s Jason suddenly acquires a lot more narrative vigour in its last two

books (for those who have managed to get that far) one suspects that something

personal may be going on here too.

Perhaps in this case we have a reverse Sohrab and Rustum situation. The episode in which Medea persuades King

Pelius’s three daughters to chop him up into small pieces is certainly striking

enough; did Morris, as a father of two daughters, fear that they might somehow

one day overwhelm his identity? And in

the very last book, as a mid-life Jason contemplates abandoning Medea for the

much younger woman Glauce, there is again real intensity in Morris’s story-telling. The usual biographical account of his

marriage is all about his depression at Jane gradually abandoning him; but the

last book of Jason might suggest that

he knew extra-marital temptation on his own side at first hand too.

Next year, 2017, is the 150th

anniversary of the publication of Morris’s Jason, so it might be well worth the William Morris Society organising some systematic,

celebratory attention to the poem.

1 comment:

Great bblog post

Post a Comment